The legal battle initiated by New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees in 2018, culminating in a nearly $6 million verdict in 2021 against a San Diego jeweler for overpriced fancy color diamonds, has reignited discussions within the diamond and jewelry community about the investment aspect of gems. This development met with an appeal from the jeweler, underscores the complexities of investment in fancy color diamonds. The Fancy Color Research Foundation (FCRF) continues to field inquiries, highlighting the need for clear strategies and expectations for all sides in these high-value transactions.

According to the lawsuit filed on April 2nd, Mr. Brees alleges that a San Diego retailer did not “act in good faith” by brokering a deal worth $14,535,004 of “investment grade” fancy color diamonds, with what he claims was an unreasonably high profit margin. An independent appraiser valued the jewelry at $6.5 million. [Click here to read the lawsuit]

The topic of investing in fancy color diamonds is intricate and exceeds the scope of this brief article. Therefore, we aim to distill the concepts to elucidate the primary aspects and instill a foundational comprehension of the diamond supply chain—crucial for navigating this specialized market. A rudimentary grasp of the wholesale domain and essential terminology is indispensable for anyone looking to penetrate the nuanced world of this unique industry.

Investment is traditionally seen as the allocation of capital with the expectation of obtaining returns, be it through interest, income, or asset appreciation. The pursuit of such gains from gemstones outside the structured environment of wholesale trade, poses significant challenges, especially for private clients who are external to the industry’s supply chain.

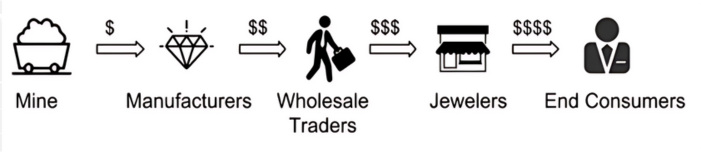

Within the supply chain, a diamond undergoes four distinct phases of enhancement before reaching the final buyer. Throughout these stages, its value is augmented due to various processes of transformation and refinement.

Bearing the traditional concept of investment in mind, it’s crucial to adjust expectations around luxury items like fancy color diamonds. Direct financial yields or fast appreciation are unlikely. However, with judicious selection, these items may appreciate in value over a long time. The Fancy Color Diamond Index substantiates this, showing a remarkable appreciation in the wholesale prices of pink and blue fancy color diamonds—398.4% and 250.5% respectively—over the past 19 years. Yet, translating such wholesale market gains into profits for those outside the supply chain proves daunting. Private collectors aiming to sell their investments upstream back to wholesalers or retailers must navigate through the accrued profit margins that have been applied to their diamonds at every step from wholesale to retail.

Without access to a dedicated platform for trading or liquidating their investments profitably to other private clients, they must rely on the long gradual appreciation of their assets over time—a process that requires patience and a strategic outlook.

Profit from fancy color diamonds can indeed be realized by end consumers, albeit with a requisite degree of patience. Imagine a scenario where a retailer acquires a diamond for $1,000 and sells it to a consumer for $1,500. For the consumer to see a profit, the market value of the diamond would need to substantially rise—let’s say to $2,900. If the consumer then decides to sell the diamond back to the retailer for $2,000, they not only secure a profit from their initial investment but also provide an opportunity for the retailer to earn a margin upon resale. This dual potential for profit encourages the retailer to engage in the buy-back, but only if the resale margin is sufficiently attractive to justify the transaction. Without such a margin, the retailer’s motivation to repurchase the diamond diminishes, underscoring the delicate balance of interests in these transactions.

Additionally, auctions often appear as an attractive avenue for private clients looking to liquidate their gems, offering a transparent process with the allure of potentially igniting a bidding war between eager buyers. However, in reality, this route frequently results in the lowest returns for sellers. The majority of attendees at fancy color diamond auctions are wholesalers on the lookout for bargains. Coupled with the necessity to subtract a significant 20% fee from the buying price, sellers find that this seemingly opportune platform can significantly diminish their expected profits, challenging the notion of auctions as the most lucrative or desirable method for selling high-value gemstones.

Fancy color diamonds acquired at retail prices 15 years ago or more have sometimes been resold to the trade at a profit. Enthusiasts who invested in fancy color jewelry have not only enjoyed their beauty while celebrating their success over the years but have also managed to sell them for more than their original purchase price. This situation represents an ideal outcome, highlighting that realizing a profit from such investments usually demands a considerable period. Hence, these alternative investments are often more about long-term wealth preservation than about serving as traditional investments.

Misconceptions Lead to Disappointment

The Fancy Color Research Foundation (FCRF) has been and continues to be engaged in B2B fancy color diamond valuations and the handling of legal disputes involving color diamonds. Misinterpretations or misapplications of terminology frequently cause confusion. This section is dedicated to clarifying several key terms that emerged during different lawsuits, providing essential insights to properly contextualize the issues at hand.

The term ‘Market Value‘ is often misunderstood, as it can represent several different prices for the same diamond, each from a distinct viewpoint within the supply chain. In essence, the ‘market price’ is not a fixed number but rather varies according to the position of the speaker in the market. For instance, the price a manufacturer considers as the market price will not be the same as the price perceived by a retailer. This discrepancy underscores the importance of understanding the specific context when discussing the market value of a diamond.

Wholesale Price: This is the price per carat at which wholesalers purchase diamonds within the diamond bourse. It’s a critical figure that forms the baseline for subsequent pricing in the supply chain.

Retail Price: This refers to the cost to retailers when they acquire a diamond from wholesalers. It’s an intermediary stage that includes the initial mark-up from the wholesale price.

Retail Selling Price: This is the price at which the diamond is offered to the end consumer, incorporating a substantial retailer margin. It’s the final price point and the one most familiar to consumers, reflecting not just the cost of the diamond itself but also the retailer’s operational expenses and profit margin.

The label “Investment Quality Diamonds” is nuanced and should be reserved for use by wholesalers who have the subtle indicators of a diamond’s potential to appreciate in value. Generally, a fancy color diamond deemed to have investment quality doesn’t just fulfill most criteria on a gemological report; it also exhibits exceptional visual characteristics as per the IDU grading standard, distinguishing it in both quality and potential market value.

“Professional Appraiser” describes experts who are well-versed in a broad array of products and adept at gathering price information from a variety of sources. For fancy color diamonds, however, their reliance on auction prices of similar examples or consultations with wholesalers without diving into the visual aspects derived from the IDU grading system, as primary valuation methods does not capture the diamond’s retail selling price accurately. This approach can result in evaluations that do not truly reflect the diamond’s real value, potentially misguiding owners and investors with incorrect or misleading appraisals.

In summarizing this discussion surrounding fancy color diamonds as an asset class, it’s imperative to underscore several critical insights. Firstly, fancy color diamonds are best approached as vehicles for wealth preservation rather than conventional investments. Their enduring value offers a safeguard against inflation and economic fluctuations, yet they embody a market dynamic distinctly different from traditional investment assets. Secondly, for enthusiasts keen on integrating fancy color diamonds into their investment portfolio in a more transactional manner and with a higher liquidity, collaboration with a reliable wholesaler is essential. This partnership is crucial for navigating the trading landscape effectively, ensuring access to the best prices and market insights.

The saga of Drew Brees underscores a cautionary tale about the complexities of diamond investment at the retail level. Brees’ experience highlights the premium that private collectors often pay over wholesale prices, a disparity compounded by the lengthy duration required for the investment to mature. Moreover, the misuse of the term “investment” by the wholesaler, coupled with an unrealistic timeline for appreciation, serves as a potent reminder of the need for clarity and honesty in transactions.

Lastly, the role of professional appraisers in the valuation of fancy color diamonds is fraught with serious limitations. Lacking a deep understanding of the specialized grading systems and the intricacies of the supply chain, including retail margins, appraisers can inadvertently provide assessments that do not accurately reflect the retail buying price of these gems. This misalignment not only leads to potential financial loss but also underscores the necessity for specialized knowledge in the evaluation of fancy color diamonds.