“Bubbles” in diamonds are an interesting phenomenon occurring often in fancy color diamonds, particularly in pink diamonds originating in Africa. However, bubbling can occur in all diamonds, making it relevant to all professionals in the industry. Although “bubble” inclusions do not affect fancy color diamond price behavior, it is important to understand them: the collective misconception that diamonds hold gas bubbles in their internal structure has forced many manufacturers to develop strange theories and practices as part of their ‘risk management’ strategy.

When manufacturers identify an inclusion that appears to be a ‘bubble’, they laser drill a channel to the bubble to release pressure and tension because of concern that the gas will expand due to the high temperature, and crack the stone during the polishing process. This misconception is even adopted by insurance companies who support the procedure in case they need to insure a stone.

One of the biggest misnomers in the diamond industry is the term bubble. It has generated a pervasive misconception that certain features visible within a diamond are trapped gas bubbles. This is NEVER the case. At the great pressures and temperatures that diamonds form under, it is not possible for anything to exist in the form of a gas. Only solids and liquids exist under these extreme conditions. These bubbles are actually inclusions of other minerals that became trapped by the diamond as it grew.

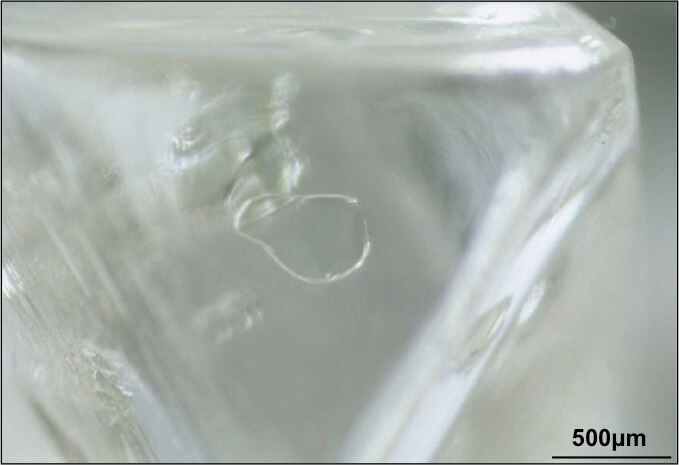

These inclusions represent fragments of the rocks in which the diamonds grew, or they can be the products of the same fluids that the diamonds themselves grew from. The reason for people referring to these inclusions as bubbles is that they look similar in shape and transparency to gas bubbles and can appear empty (picture 1). When the inclusion is as transparent as the diamond surrounding it, it is not obvious that there is anything solid within it. However, there always is.

One reason we know these inclusions are not gases is because they have been extensively studied for decades. Though my work only extends back about 12 years, these studies have been done by some of the most advanced scientific laboratories in the world. This work can be carried out while the inclusions are still trapped within the diamond. Spectroscopic techniques like infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy that look at the vibrations of atoms, which are capable of identifying fluids and gases, confirm these transparent inclusions as solid minerals.

![Image 2: This diamond also contains two inclusions of colourless olivine. But this time they have had the morphology of the diamond imposed upon them, giving them more defined crystal faces and making them look less like a ‘bubble’. [Image taken by Dr Dan Howell, sample provided courtesy of Dr Jeff Harris, University of Glasgow.]](https://www.fcresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/sample9_refl-700x525.jpg)

The extreme pressures and temperatures of diamond formation mean that they can never contain an inclusion that consists purely of gas. There is only one scenario in which an inclusion can contain gas, and that is when the inclusion is initially a fluid. As the diamond is transported to the surface, the temperature decreases. This causes minerals to grow from the trapped fluid, and also for some gases to absolve. This produces an inclusion containing several mineral crystals and a gas that looks like a void in the diamond. These fluid inclusions are very common in coated diamonds, where there is a dirty layer (or coat) surrounding a gem-quality diamond core. The occurrence of this type of incredibly small inclusion in gem-quality diamond is phenomenally rare.

There are probably two key scientific advances that have come from the study of solid mineral inclusions in diamonds that are of significance to the industry. The first would be an understanding of the chemical and physical environment in which diamonds are growing. This has allowed the identification of chemical indicators to guide exploration. Kimberlites, the volcanic rocks that host diamonds, are rare but a diamondiferous kimberlite is even rarer. Instead of trying to find diamonds, exploration companies look for more abundant minerals (e.g. garnet), which might indicate the presence of a kimberlite. By then analyzing it and studying its chemistry, it is possible to determine whether the kimberlite it came from is likely to host diamonds.

The second significant contribution to come from studying inclusions in diamonds is determining the great age of some diamonds. While rough constraints can be placed on some diamonds’ age by studying their nitrogen impurities (a topic for another article), it is only by analyzing specific types of mineral inclusions that we have determined that diamonds have been growing within the Earth as far back as 3 billion years ago. This antiquity has been a key factor in diamond becoming the most sought after and valuable gemstone. So whilst you might loathe the presence of an inclusion that lowers the clarity grade, to some scientists, it is more valuable than the diamond itself…

While this level of study of diamond may seem academic to some, misconceptions about diamonds can cause myriad problems throughout the trade. This is why we feel it is vital to remain as informed as possible and thank the FCRF for the opportunity to share our knowledge with the trade.

Daniel Howell, Ph.D.

Co-Founder and Chief Scientist, Diamond Durability Laboratory

Dr. Daniel Howell is a co-founder of the Diamond Durability Laboratory (www.DDL.diamonds) and research scientist at the University of Bristol (UK). He has over 10 years of experience researching diamonds, working on topics such as diamond growth, internal stress and causes of colour.

[1. ] Image 1: This seemingly empty ‘bubble’ is actually a colourless inclusion of olivine. [Image provided courtesy of Dr Jeff Harris, University of Glasgow.]